Rashi at the beginning of the Torah asks the following question

Rabbi Isaac said: The Torah should have commenced with the verse (Exodus 12:2) “This month shall be unto you the first of the months”, which is the first commandment given to Israel. What is the reason, then that it commences with the account of the Creation?…

We are all familiar with the answer. Creation was written to teach us that the Land belongs to God who apportions it to whom He sees fit, which, by the way, is an enduring rejoinder to secular Zionism which professes that secular Jews somehow have a right to the Land while ignoring the Torah that gives them title to it.

But I would like to focus on something else.

Rashi is assuming that the Torah is primarily a Code of Law, the same way Torah Jews typically conceive of it, and so is bothered that the Torah commences with the narrative portion of Creation. But this assumption itself raises a difficulty. Why does Rashi argue that the Torah should have started with “This month shall be unto you the first of the months”, a dialogue between Hashem and Moshe which is part of the Exodus narrative? If we are looking at the Torah as a Code of Law, wouldn’t it be more logical for the Torah to be organized in the typical style of a legal code- for example, the Rambam- to start with the existence of God and the various commandments related to that, and then to continue list of the commandments by topic- or l’havdil, the Code of Hammurabi- a brief preamble about the authorship, and then a list of laws? Wouldn’t this be much more straightforward than inserting the laws into a complicated narrative involving Moshe, the Jewish people, the Exodus, and the desert sojourn?

And when we investigate what the Torah is, it really does seem quite strange. Is the Torah a book of stories or is it a book of law? On the one hand, it is definitely clear that major portions of the Torah are meant to be legal and ritual texts, as Rashi assumes, instructing the reader of the book in the details of religious practice. On the other hand, other major portions of the Torah are clearly meant to teach Jewish history. But unlike a normal code of law, such as lehavdil Hammurabi, the legal/ritual portions are almost always inextricably woven together with the history. Thus, when we read

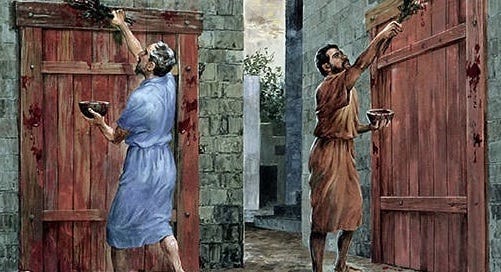

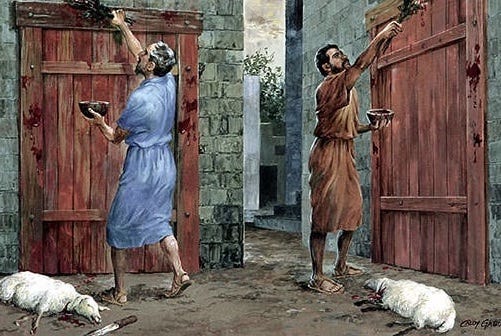

And the Lord spoke to Moshe and Aharon in the land of Miżrayim, saying, This month shall be to you the beginning of months: it shall be the first month of the year to you. Speak to all the congregation of Yisra᾽el, saying, On the tenth day of this month they shall take to them every man a lamb, according to the house of their fathers, a lamb for a house: and if the household be too little for a lamb, let him and his neighbour next to his house take it according to the number of the souls; according to every man’s eating shall you make your count for the lamb. Your lamb shall be without blemish, a male of the first year: you shall take it from the sheep, or from the goats: and you shall keep it until the fourteenth day of the same month: and the whole assembly of the congregation of Yisra᾽el shall kill it towards evening. And they shall take the blood, and put it on the two side posts and on the upper door post of the houses, in which they shall eat it. And they shall eat the meat in that night, roast with fire, and unleavened bread; and with bitter herbs they shall eat it. Eat not of it raw, nor boiled at all in water, but roast with fire; its head with its legs, and with its entrails. And you shall let nothing of it remain until the morning; and that which remains of it until the morning you shall burn with fire. And thus shall you eat it; with your loins girded, your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it in haste; it is the Lord’s passover. For I will pass through the land of Miżrayim this night, and will smite all the firstborn in the land of Miżrayim, both man and beast: and against all the gods of Miżrayim I will execute judgments: I am the Lord. And the blood shall be to you for a token upon the houses where you are: and when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and the plague shall not be upon you to destroy you, when I smite the land of Miżrayim. And this day shall be to you for a memorial; and you shall keep it a feast to the Lord; throughout your generations shall you keep it a feast by ordinance for ever. Seven days shall you eat unleavened bread; … therefore shall you observe this day in your generations by an ordinance for ever…

-while it is readily apparent that these are not just instructions to the Israelites at the time of the Exodus, but instructions to present-day readers, directing them how to perform the Pesach and to observe the Holiday, at the same time, these very verses are also about God smiting the Egyptian firstborn and skipping the blood-marked Israelite homes, and the author (Moshe) leaves it ambiguous how the Pesach should be observed in future years when God is not smiting firstborns. And Pesach is but one example. Most of the other laws of the Torah share this same characteristic. The Ten Commandments are part of the revelation at Sinai, as is the portion of Mishpatim (civil law). The entire Vayikra is against the backdrop of the construction of the Mishkan and consecration of the Leviim. The special privileges of Cohanim are part of the narrative of Korach’s quarrel. Many of the laws of Devarim are preparation for entering the Land of Israel. So this leads to the question- why was the Torah written in this unique style that no normal legal code shares?

To answer this, let us return to the Pesach lamb. One thing we notice is that the laws in Shemos don’t make any mention of the Temple or central shrine where the lamb should be brought. Presumably, the Torah means for it to be observed in one’s home, just like the original Pesach lamb in Egypt. On the other hand, in Devarim (16:1-2), the Torah states:

Observe the month of Aviv, and keep the passover to the Lord thy God: for in the month of Aviv the Lord thy God brought thee forth out of Miżrayim by night. Thou shalt therefore sacrifice the passover to the Lord thy God, of the flock and the herd, in the place which the Lord shall choose to place his name there.

Clearly, the Torah is alluding to the Mishkan or Temple, where it means for the Pesach to be brought.

Does this contradict the instructions in Shemos? According to the Bible critics, it certainly does, and is evidence of multiple authorship, in which the Deuteronomist had a different version of the Pesach than the author of the Exodus verses. But from a normal Mesorah-based perspective, there is no discrepancy- the instructions in Devarim simply complement those in Shemos, rather than contradict them.

However, when one realizes how the laws of the Chumash are based on the overall historical narrative, as we discussed, it is quite obvious why this is no contradiction in the first place. The verses in Shemos don’t mention the “the place which the Lord shall choose to place his name there” because such a concept didn’t exist yet. The Pesach in Shemos, while an eternal Law, was commanded to the Jewish people of the generation of the Exodus, who knew nothing of the Mishkan, which they would build within a year, and certainly not of a Temple in the Land of Israel. It is only in Devarim, once the nation had a Mishkan, and were furthermore informed that there would be a more permanent Temple in the Land of Israel, that the Pesach directives mention it. And even then, there is no mention of “Zion” or “Jerusalem”, only “the place which the Lord shall choose to place his name there”, presumably because these were names that the Israelites were yet unfamiliar with.

In fact, this supposed “contradiction” is a major problem for Bible critics- Why would the redactor of the Bible leave such a major discrepancy in religious instruction? Should the Pesach ritual, the all-important commemoration of the Exodus, which merited being mentioned multiple times in the Prophets, be performed at home or be performed in the Temple? Instead of deciding on one, the redactor included two contradictory versions. This is completely useless as far as instructions go. Who would compose a code of law like this? What would be the purpose of such a book? The Chumash is not like the Mishna which explicitly casts itself as a work intended to record disputes, but depicts itself as the eternal Law of Moses- and yet contains this glaring contradiction, along with many others. Even worse, the Torah from mid-Vayikra (Chapter 17) and onward is very opposed on personal sacrifices, insisting that all offerings only be brought in the Sanctuary. This is even more explicit in the Prophets, where the Pesach is shown as a symbol of the centralization of worship in the Temple of Jerusalem. How could the redactor, who was very aware of this philosophy of centralization, leave a remnant of “backyard sacrifices” in a book which clearly comes to combat this practice? It is only according to the Mesorah, in which the original Pesach was commanded before there was any central shrine, that this makes any sense at all.

And in fact, it is only according to the Mesorah that the entire style of the Chumash makes sense in the first place. According to the Mesorah, it is obvious why the laws are organized the way they are, and this is because this is how they were commanded God, each in their proper time and place. Thus, Moshe first introduced the laws of the Pesach during the Exodus, and this is how they were recorded in the Torah for posterity. God spoke the Ten Commandments at Sinai, and this is how they were recorded in the Torah. The Mishkan was constructed, and it is here where the prescriptions for sacrifices were commanded. The daughters of Tzelofchad beseeched Moshe for a portion of the Land, and it was here that he instituted the laws of inheritance.

But in the opinion of the Bible critics, Moses is a mythological figure who never spoke with God, never issued any commands, never wrote anything, and didn’t exist. The customs and rituals of the Torah developed over many centuries among a group of indigenous Canaanites who called themselves Judeans and Israelites, and who developed fanciful myths about their own origins. The point of writing down these customs and rituals would not have been to introduce new religious practices, but to collect and organize these pre-existing traditions in written form. In which case, the way the Torah is organized, the archaic terms it uses (such as referring to Jerusalem as “the place which the Lord shall choose to place his name there”) and the injunctions of obsolete practices (such as performing the Pesach in the home, with blood markers to prevent God from smiting the occupants), make no sense at all. The entire organization of the Torah, the language it employs, and the structure and content of its law portion all suggest the Torah is of ancient vintage and was instructed to an ancient generation, as is readily apparent from the text, and as is believed by all Torah Jews to this day.

Very well written!

The Documentary hypothesis has many problems, but yours hits the nail on the head. Even before we know the Torah is Divine, its wisdom is blatantly clear. Even before we use the multiple layers of TSBP we can see that the Torah is a breakthrough document. If it was written by some wise people, how did they not see the glaring contradictions that waited for Wellhausen? The inconsistencies should tell us that there are deeper layers of meaning, themselves demanding a TSBP to explain them.

I am cutting and pasting a Goyishe joke here to express a point:

Three sons left home, went out on their own, and prospered. Getting back together, they discussed the gifts they were able to give their elderly Mother. The first said, “I built a house for our mother.” The second said, “I sent her a Mercedes with a driver.” The third smiled and said, “I’ve got you both beat. You remember how mom enjoyed reading the Bible? And you know she can’t see very well. So I sent her a remarkable parrot that recites the entire Bible. It took the elders in the church 12 years to teach him. He’s one of a kind. Mama just has to name the chapter and verse, and the parrot recites it.” Soon thereafter, mom sent out her letters of thanks:*

“Milton,” she wrote one son, “The house you built is so huge. I live in only one room, but I have to clean the whole house.”

*“Gerald,” she wrote to another, “I am too old to travel. I stay most of the time at home, so I rarely use the Mercedes. And the driver is so rude!”

*Dearest Harry,” she wrote to her third son, “You have the good sense to know what your mother likes. The chicken was delicious.”

Hashem gave us a Torah with many layers of wisdom and depth. Every contradiction that we see, brings us to deeper understanding and more chidushim. Every time a word seems superfluous, we learn a new Halacha and understand Ratzon Hashem better. Part of the great gift of the Torah is its difficulty.

Then along came Johann Eichorn, Jean Astruc, and other 'scholars' and took the gift and stomped on it, while claiming to be studying it. They ate it like it was chicken.

איזהו שוטה המאבד מה שנותנים לו

Happy, if I may, I would add to your point (perhaps a כל המוסיף גורע?) what the גר"א says in אדרת אליהו beginning of דברים. He sets up the picture that the Five Books are actually בעיקר three, שמות, ויקרא and במדבר. He explains that בראשית is like the introduction (elsewhere he explains that אדם is the beginning of mankind, נח is the תחילת האומות and the אבות and שבטי קה are תחילת ישראל, with which בראשית concludes). And דברים is like the summary of מרע"ה. In the middle we have these three main ספרים with a ראש, תוך וסוף, as שמות is the beginning and set up of כלל ישראל, through their growth, שיעבוד וגאולה, afterwards מתן תורה and הקמת המשכן. All the מצוות therein are related to this setup (עשרת הדברות are like the beginning of everything, which כולל everything, משפטים are דרך ארץ קדמה לתורה and the setup of the משכן and information about the בגדים are all prior to ויקרא to set up the scene for the עבודה).

ויקרא is עיקר תורה, with the bulk of the מצוות, especially the קרבנות which are the shpitz עבודת השי"ת בעולם הזה. Last we have במדבר which is kind of like a wrap up, with instructions to go to א"י and be the כלל ישראל that we know to keep said Torah in it's proper place.

Point I'm bringing out, is that the story of the building of כלל ישראל as described, in perfect tangent with the מצוות given, each commanded in their proper point of that growth of כלל ישראל and connection to הקב"ה, are one beautiful story of our קשר with Him, and how to continue growing with Him throughout our own lives.

(One last point: the storyline which begins with מעשה בראשית is how השם sets up the world with all the history of ספר בראשית, all in order that when the time is ripe, כלל ישראל can step into the picture and conquer א"י and become the center of the world as they are supposed to be. כח מעשיו הגיד לעמו isn't just an answer to one specific question, why "בראשית" over "החדש הזה לכם." It is the answer to explaining the very question of why is the Torah presented as a story if it is indeed a book of laws, and the answer is that the world is setup to be anti-God, with the אומות in charge, and then we, כלל ישראל, step in and perfect it through following His laws. The split between us and the אומות and our role in that is wonderfully interwoven into the fabric of the Torah, that we end up battling and conquering the עובדי ע"ז, those who fight Hashem, and take over and establish Him as the true King whom He really was the whole time, along with His רצון, the עשיית המצוות, the center of the whole תורה.)