It’s always a good time to battle the heretics, even on Erev Yom Tov! Here is an oldie but goodie from Rabbi Herschel Grossman, where he tackles Marc Shapiro’s distortions. Rabbi Grossman graciously allowed us to copy the full text of his paper. Since we didn’t write the paper, we cannot take responsibility for everything contained in it, and any questions can be addressed to Rabbi Grossman himself, but we most certainly agree with the overall message. For full disclosure, Shapiro responded to this paper, and Rabbi Grossman responded to his response, all of which we link.

Links:

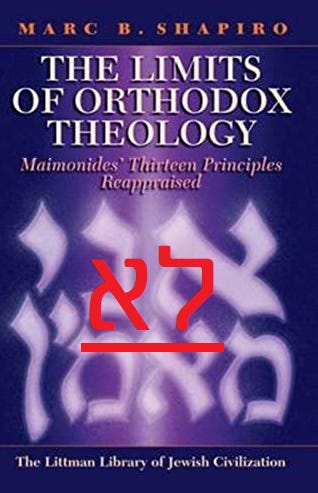

Original paper from Rabbi Grossman: THE LIMITS OF ACADEMIC CRITICISM A Review of The Limits of Orthodox Theology

Response by Shapiro #1: Response to Criticism, Part 1

Response by Shapiro #2: Response to Criticism, Part 2

Response by Shapiro #3: Response to Criticism, Part 3

Response to Shapiro’s response from Rabbi Grossman: PRE-CONCEIVED CONCLUSIONS - A Rejoinder Regarding The Limits of Orthodox Theology

THE LIMITS OF ACADEMIC CRITICISM

A Review of The Limits of Orthodox Theology1

By Rabbi Herschel Grossman

In recent years, there have been many works published by academics in the realm of Torah and Jewish literature. These works appear on their surface to be authoritative and well-researched; they are replete with footnotes containing references to works often unfamiliar even to the learned. Many of the conclusions of these works are at variance with accepted Torah teachings, but because of the scholarly reputation of their authors, especially if they are Orthodox Jews, they are often accepted by the Torah observant public in unquestioned faith.

Rabbi Grossman is the former principal of Ohr Yosef Torah High School in New Milford, NJ and studies and teaches in Yerushalayim.

1 By Professor Marc Shapiro. Oxford, uK: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004. Dr. Shapiro holds the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Chair in Judaic Studies at the university of Scranton.

The academic approach to matters of Torah learning is radically different from that of the talmid chochom. A talmid chochom. sits, as it were, at the feet of the earlier commentators, with the clear assumption that the earlier commentators were fluent in every part of the Talmud and understood it better than he does. If a difficulty or inconsistency in the words of the earlier authorities presents itself, the talmid chochom assumes that the fault is with him, the student, not with the master, and that it is incumbent upon him to make every effort to justify the words of the master.

On the other hand, many academics build their reputations on discrediting previously accepted theories. When an apparent inconsistency in the writings of the earlier authority presents itself, these academics rush to conclude that either the master erred, or that he invented an idea for personal, historical or political reasons. Interpretations of difficulties in the writings of earlier authorities offered by world-class Talmudic scholars throughout the ages are cavalierly dismissed as “obviously incorrect,” “forced” or “re-interpretations.” Though these judgments are often made without proof, this academic poses as the ultimate authority, with sufficient wisdom to dismiss or accept anything in his purview.

In short, for the talmid chochom, a difficulty in the words of the authority creates a challenge for him to discover the true meaning of the authority. For many academics, a difficulty is proof that the authority is wrong.

Professor Marc Shapiro’s The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles Reappraised is an example of this sort of scholarship. The book is a study of the Thirteen Principles of Jewish faith by the Rambam. Its thrust is that the Rambam erred in codifying these Principles and it “takes issue with the widespread assumption that Maimonides’ famous Thirteen Principles are the last word in Orthodox Jewish theology.”[1] While some earlier scholars have disputed whether some of the Principles deserve to be listed as basic to Judaism but have all conceded that the tenets expressed by the Principles are correct, Shapiro goes further and purports to demonstrate that, in traditional Jewish sources, many “scholars … thought that Maimonides’ Principles were wrong, pure and simple.”[2] Shapiro concludes that the Rambam’s formulation of the underlying beliefs of Judaism was his own innovation. Even such basic tenets as the belief in God’s unity, or in God’s non-corporeality, says Shapiro, are the Rambam’s own assertions and subject to dispute, with no firm basis in the Torah or in Chazal.

In his lengthy introduction, Shapiro states that he is following in the footsteps of Louis Jacobs and Menachem Kellner,[3] academic scholars whose prior elucidations of Maimonides’ Principles have challenged the prevailing notions in the traditional community.

Kellner believes that academics, including himself, understand the Rambam better than world-famous Torah authorities. In his words:

My colleagues and I, academic Rambam scholars, despite the disputes among us, understand the Rambam better than people like Rebbe Elchanan Wasserman. The Rambam is among the few individuals about whom it can be said that if he has adopted a certain position, that position is now “kasher” from a Torah perspective. From this we can conclude that my colleagues and I understand one Torah perspective better than Reb Elchanan and his colleagues, the contemporary Roshei Yeshiva.[4]

Shapiro, who mocks the opinions of Rabbeynu Nissim,[5] R. Moshe Feinstein,[6] Chazon Ish,[7] Arizal[8] and R. Ya’akov Emden,[9] among others, goes one step beyond Kellner in his belief that he, Shapiro, is better able than Rambam to interpret explicit verses of the Torah (as we shall see below).

Shapiro does not refrain from adducing explicit Talmudic passages as contradictions to the Rambam, presuming that the Rambam overlooked or ignored them, something which innumerable Talmudic scholars in past centuries have considered inconceivable. Thousands of pages have been written to justify any inconsistency between the Rambam’s writings and any passage in both Talmuds. Shapiro is unimpressed by all these arguments; nor is he averse to dismissing Rambam’s opinion based on his, Shapiro’s, own reading of a Talmudic passage, even where there is no doubt that the Rambam had a different reading for it. An academic, he obviously feels, is privileged to interpret the Talmud better than the Rambam was, even where this presumption leads to bizarre conclusions.

Shapiro is an outstanding and established professor of Jewish studies. Although he is to be commended for the amount of research he has invested into his work—the citations he has amassed are voluminous—it seems that many of the references were culled from secondary sources without examining the originals. As will be seen below, it is not uncommon for him to cite sources which, upon examination, emerge as inaccurate, irrelevant or even contradictory to the point he himself is trying to make.

To analyze the errors in this book would require a book in itself, nor is this the purpose of this article. The purpose is to show the lack of basis for Shapiro’s assertions (1) that the Rambam’s Principles have no basis in Talmudic literature; (2) that he created these Principles either to advance his philosophic conclusions or for polemic purposes; and (3) that many authorities thought the Principles “were wrong, pure and simple.”[10]

I. ARE THE PRINCIPLES AN INNOVATION?

Underlying the book’s analysis of the Principles is the thesis that the Thirteen

Principles are the Rambam’s innovation and have no source in the Talmud.[11] Shapiro writes:

I don’t believe there is any Talmudic basis for the Rambam’s unique conception of Ikkarim … understanding of faith as the basis of everything. I believe it was a complete innovation which is at odds with the tenor of the talmudic texts and certainly of the biblical texts which know nothing of this. This is not just something mentioned by modern academics, but is also pointed out by traditional commentators.[12]

Shapiro writes this despite the fact that an array of classic scholars, among them Alshich,[13] R. Moshe Chagiz,[14] Beney Yisoschar[15] and Mabit believe otherwise. The latter, in a section of his Beys Elokim devoted to the Principles, begins his discussion with this comment:

All the main Principles of the Torah and its beliefs are either explicit or hinted at in Torah, Prophets, the Hagiographa, and in the words of Chazal received from a tradition; in particular, the three Principles which include them all.[16][17]

Questioning the Principles

Nothing shows more clearly that the Rambam based his Principles upon the Talmud than the fact that in Hilchos Teshuvah,18 he lists the various heretics under three classifications: min, apikores and kofer baTorah, all of whom lose their share in the World to Come. Obviously, each group violates a particular fundamental of faith, or else why would they be listed separately? Shapiro explains this by saying: “For his own conceptual reasons which have no talmudic basis, Maimonides distinguishes between the epikorus, the min and the kofer batorah.”[18] But these terms are not, as Shapiro would have them, the Rambam’s inventions. They are taken from an explicit passage of the Talmud in Rosh haShanah 17a which lists these three classes of heretics as those who lose their portion in the World to Come.[19] They are obviously not a product of Rambam’s “conceptual reasons.”

Rambam codified the Talmud’s categories of heresies in Hilchos Teshuvah 3: 6-8 and interprets them as referring to the three categories of, respectively, denial of God, denial of Revelation and denial of the truth of Torah.21

Shapiro questions if Maimonides truly “regarded the Thirteen Principles as his final statement on the fundamentals of Jewish faith,”22 for in Shapiro’s reading of Rambam, “one who has heretical thoughts but conducts himself as a good Jew does not lose his share in the world to come.”23 Rambam in his Commentary to the Mishna says explicitly otherwise,24 but Shapiro claims that Rambam retracted in his Mishneh Torah. His proof that Rambam did not regard “the Thirteen Principles as his final statement on the fundamentals of Jewish faith”25 is from the process of conversion codified by the Rambam in his Hilchos Issurey Bi’ah. “[O]ne must wonder,” states Shapiro, “why there is no mention of the Principles in his discussion of what a future convert should be taught.”26

In describing the procedure for acceptance of a convert, and warning him first of the difficulties a member of the Jewish people must endure, Rambam continues: “We inform him of the fundamentals of the faith which are the

punishment in the Talmud is מורידין ולא מעלין, Rambam understands these differently, as specific heretical beliefs and he classifies them in three distinct categories. Evidence that the Rambam indeed derived his categorization of the Principles from Avodah Zarah 26b is in the gloss of the Vilna Gaon, note 11 to Shulchan Aruch, Y.D. 158:2, where he points to Rambam’s Hilchos Teshuvah 3:8 in support of the Shulchan Aruch.

21 The question as to the consistency of the Talmud’s use of these terms is addressed by Lechem Mishneh in Hilchos Teshuvah 3. Belief in the coming of the Mashiach and belief in Resurrection are also specifically listed, each in a separate category.

22 Limits, p. 7.

23 Ibid., p. 8.

24 Sanhedrin, chap. 10, where the Principles are listed and elucidated.

25 Limits, p. 7-8.

אומרים לו: הוי יודע שהעולם הבא אינו עשוי אלאIbid. The Talmud (Yevamos 47a-b) states: 26 לצדיקים, וישראל בזמן הזה אינם יכולים לקבל לא רוב טובה ולא רוב פורענות ואין מרבין עליו ואין מדקדקין עליו...ומודיעין אותו מקצת מצוות קלות ומקצת מצוות חמורות.... ומודיעין אותו עיקרי הדת שהוא יחוד ה'The Rambam (Hilchos Issurey Bi’ah 14:2) codifies this as: ואיסור עבודה זרה ומאריכין בדבר זה. ומודיעין אותו מקצת מצות קלות ומקצת מצות חמורות ואין מאריכיןבדבר זה....

unity of God and the prohibition against idolatry, and we elaborate on this.”[20] The Talmud, the source of this ruling, says: “And he is informed of severe and light sins,” but mentions nothing regarding the unity of God or idolatry.[21] According to Shapiro, this statement indicates that the Rambam retracted the opinion in his Commentary regarding the beliefs essential to being a Jew.[22] Otherwise, since the Rambam added to the Talmudic prescription [by adding the Principles regarding God’s unity and idolatry—HG], then why did he not add all of his Principles?

This argument demonstrates a misconception of the structure of the Rambam’s work. The Rambam himself states explicitly in his letters[23]—and so it is axiomatic to Torah scholars—that he never made a statement in his Mishneh Torah which did not have a source in the Talmud. Whenever he records his personal opinion, he prefaces it with the words, yeyra’eh li—“it would appear to me.” Anything in his Mishneh Torah that seems different from the Talmud is due to the Rambam’s unique interpretation of the particular passage of Talmud.[24] Thus, the question, “If the Rambam added to the Talmudic prescription, why did he not add the other Principles?”[25] is not applicable.

The Rambam’s source is the teaching of Rebbi Elazar[26] describing the dialogue between Naomi and Rus:

“[Naomi said:] ’We are prohibited to serve idolatry,’ [and Rus responds;]

’Your God is my God.’”

The Rambam understands this discussion as referring to the Principles of idolatry and God’s unity. Apparently, adopting these two Principles is the essence of conversion to Judaism.[27] These might be a mere sample of other laws and ideas that we also mention—as implied by the Rambam’s concluding phrase, “and we elaborate (u-ma’arichin) on this.” The Rambam is codifying that which the Talmud prescribes as integral to the conversion process, thus, one cannot ask why the Rambam did not mention other Principles of faith– which is a different subject entirely.[28]

Did Popular Acceptance of the Principles Affect Halachic Practice?

According to Shapiro, “Maimonides would be surprised that… later generations of Jews …. latched onto his earlier work;”[29] and it “is certainly one of the great ironies of Jewish history that the Thirteen Principles became the standard by which orthodoxy was judged.”[30] Finally, “the characteristic that gave them their afterlife … is precisely their outer form … Had Maimonides listed a different number of Principles in the Mishneh Torah … these would have become the Principles of Judaism.”38 In other words, after postulating that Rambam innovated these obligatory beliefs, Shapiro concludes that it was the popular acceptance of these Principles that established halachic practice.[31]

In line with the notion of this historical development which established the Principles as obligatory, Shapiro goes on to note that: “[i]t seems that there is even halakhic significance to the Principles, as [Chofetz Chaim] records that one who denies the divinity of the Torah, reward and punishment, the future redemption, and the resurrection cannot serve as a prayer leader.[32] Had Maimonides not included these Principles in his list, it is unlikely that denial of the last two, which are not necessarily of prime importance to a religious life, would disqualify one in this way.”[33]

In other words, having determined that Rambam invented these categories of heresy, Shapiro concludes that Chofetz Chaim followed this invention blindly to disqualify a disbeliever from serving as a prayer leader. Shapiro is saying that Mishnah Berurah, the foremost halachic guide of modern times, was incorrectly influenced by Rambam’s questionable classifications.[34]

However, in his haste to cast Rambam as the inventor of the Principles of Jewish belief, Shapiro seems oblivious to the many areas in Talmud where the categories of heresy have ample halachic ramification.[35]

Contrary to Shapiro’s hasty assumption, the Rambam is not the source for this Halacha. The source is the Talmud Yerushalmi, cited by the Tur as follows:

A prayer leader who skips two or three words does not have to go back to say them, except for one who does not mention “the Resurrection of the Dead,” for perhaps he is a disbeliever [kofer] in the Resurrection of the Dead, and [the blessing] “Who rebuilds Jerusalem,” for perhaps he does not believe in the Coming of the Mashiach.[36]

Obviously, the ruling of Mishnah Berurah is not an “invention” based on the Rambam.

Did the Rambam Retract His Principles?

Shapiro claims that “Maimonides himself in his later years … did not feel bound to them in the way that later became the norm in Jewish history.” He proposes this because, in Shapiro’s mind, “one would have expected Maimonides to put great emphasis upon them, quoting them in his later works and letters,”[37] and “… one would have expected them to be listed at the very beginning of his code, in the section entitled ’Hilkhot yesodei hatorah’.”[38] On the next page, Shapiro concedes that in Hilchos Yesodey haTorah, “Maimonides does indeed discuss most of the Principles;” however, they are not presented in the explicit way that Shapiro expected. Obviously, Shapiro’s expectations cannot be the basis for concluding that the Rambam retracted his Principles.

Here, too, Shapiro indicates that he is unaware of the structure of the Mishneh Torah. The entire work is an expansion of the 613 Mitzvos: The entire work is introduced by Rambam’s Sefer haMitzvos which lists all 613 Mitzvos, and each of the sections (Halachos) has a listing of the Mitzvos included therein. Consequently, there is no place to highlight the Thirteen Principles in Hilchos Yesodey haTorah, since there are explicit Mitzvos for only three of them—emunah, yichud and avodah zarah, which he in fact does list in the introduction to this section. He could not have listed all the rest since they are not Mitzvos.[39]

Another “Proof”

In another support of the claim that Maimonides in his later years did not feel bound to the Principles, Shapiro quotes a passage from the Rambam’s Ma’amar Techiyas haMeysim. In this letter, Rambam writes:

It was necessary that I clearly elucidate religious fundamentals in my works on law … I therefore published Principles that need to be acknowledged in the introduction to the Commentary on the Mishna regarding prophecy and the roots of tradition … in chapter 10 of Sanhedrin, I expounded fundamentals connected with the beginning and the end, i.e., what pertains to God’s unity and the World to Come and the other tenets of the Torah.[40]

This citation seems to prove the opposite of Shapiro’s contention that Rambam retracted his Principles. The Rambam clearly acknowledges in this letter, which was penned after he wrote the Mishneh Torah, that he considers the Principles enunciated in his Commentary as valid, and that he established these fundamentals at the opening of Mishneh Torah as well. Shapiro acknowledges this, yet still claims that “the Thirteen Principles are not set apart as being fundamentally more significant than the rest of the Commentary on the Mishna or the Mishneh Torah.”[41] He fails to cite the entire relevant passage. Just a few lines above the cited section, after explaining why he wrote his various works, particularly the Mishneh Torah, Rambam says:

After undertaking this, we saw that it would not be logical [eyno min ha-din]

… to explain the branches of the faith and to neglect its roots.[42]

Here, the Rambam states explicitly that there are roots to Judaism, namely the Principles of faith, and there are branches, the laws which derive from them. Clearly the Rambam has not retracted his opinion that there are Principles, or roots—lacking belief in which, one is missing the fundamentals of Judaism— and branches—failing to keep which makes one a transgressor but does not make one lose his connection to the roots. This is exactly what Rambam wrote in his Commentary.[43]

More “Proofs”

Shapiro continues: “… one finds different emphases, if not outright contradictions, between what Maimonides writes in his Commentary on the Mishna and what appears in his later works.”[44] Shapiro commends Leon Roth as mostly “on the mark” for writing that “there is no single one of the Thirteen Articles even of Maimonides’ alleged creed which was not rejected, explicitly or implicitly, by leading lights in the history of Judaism, including, I fancy (but only whisper the suspicion), no less a person than Maimonides himself.”[45]

Roth would have done well to keep his entire statement down to a whisper, for his assertion has no basis. There are few authorities who disagree with the Rambam’s Principles, and certainly the Rambam himself did not retract them.

It is clear from several sources that the Rambam issued corrected versions to his Commentary on the Mishna throughout his life. This is an indisputable indication that those parts which were not corrected remained his opinion. In one revision to the Principles, Rambam adds the following:

Know that the basic principle (yesod) of the Torah of Moshe Rabbeynu is that the world was brought into being (mechudash), that God formed and created it after a state of total nothingness, and if you see that I discuss the eternity of the world according to the philosophers, this is so that there be an absolute proof for His existence, as I have explained and clarified in the Moreh.[46]

The Rambam here refers to the belief in the fourth Principle—that the world is not eternal—as a Principle of faith, even after he wrote the Moreh. Indeed, in his Moreh as well, the Rambam cites the Principles several times.[47] [48]

Two authorities frequently cited by Shapiro throughout his book, Albo and Abarbanel, refer to the Moreh in explicating the Rambam’s Principles. For example, Albo writes:

And why has he not listed Creation (ex nihilo), which is the proper belief

for every man of Godly law, as he himself has explained in part 2, chapter 25 of the Guide.[49]

And Abarbanel as well writes:

…they [the Principles] are each praiseworthy beliefs on a lofty level; he mentions each individually, and refers to them in the Guide as precious ideas.[50]

Thus, these two authorities cite the Rambam’s Moreh to clarify the Principles listed in his Commentary to the Mishna. They clearly held that the Rambam held to his Principles throughout his life. Indeed, as we shall see, none of Shapiro’s sources or arguments will provide any indication to the contrary.

A Proof from the Gra

Shapiro claims to have discovered a source in the writings of the Vilna Gaon overlooked by all scholars which indicates that not all the Principles are basic to Jewish belief. He writes:

I should call attention to a significant philosophical and halakhic point which appears to have gone unnoticed. The Vilna Gaon … apparently believed that the First and Second Principles are the only true Principles in Judaism.[51]

The “unnoticed” source is the Vilna Gaon’s commentary to the beginning of Tikuney Zohar #21.[52] The Gaon comments there on the passage (cited as well in Berachos 30b) that even if a snake is coiled around one’s heel, one should not interrupt his prayer, upon which the Talmud (ibid., 33a) comments: “However, one does interrupt for a scorpion.” The Gaon explains this as an allegory to mean that one who is entrenched in sin (encoiled by a snake) can still be connected to God in prayer, while one who denies the existence of God (attacked by a scorpion)61 has removed his connection to his Creator.

The idea is that as long as one believes in the unity of God even if he has transgressed many sins, he has not rejected the entire Torah (mumar le-chol haTorah), and his prayer is acceptable, and he can be added to a minyan … However, if a “scorpion” is upon him, which refers to one who believes in idolatry and bows down to a strange god or who has had relations with a gentile woman … this is a separation from the Jewish people and Hashem removes Himself from him completely and his prayer does not ascend [to Heaven].

Apparently, concludes Shapiro, since the Gaon cites only idolatry as invalidating prayer and does not cite the rest of the Thirteen Principles, he is disputing Rambam’s classification of the others as binding fundamentals.

However, this source has no bearing on the Principles. The Gaon’s comment refers to counting one for a minyan and to having one’s prayers accepted by God. He is clearly not referring to the Principles, since he includes in the metaphor of the scorpion the sin of consorting with gentile women, which is unrelated to any Principle. The question of why idolatry and consorting with gentile women sever one’s relationship to God through prayer is open to interpretation. It might well be that to render one’s prayer invalid one must transgress the will of God with an act which rejects Judaism. Idol worship and relations with Gentile women are acts; the other Principles are beliefs not expressed in actions and are therefore not included in the image of the scorpion.

There seems to be ample reason indeed why Shapiro’s source has gone unnoticed by scholars through the ages.

Chazon Ish

There is a disagreement between Rambam and Ra’avad regarding one who believes innocently in an anthropomorphic God. Ra’avad says he is not a heretic since his belief is due to his misunderstanding of the Scriptures. The Rambam seems to dispute this and says he is a heretic. Chazon Ish writes[53] that Rambam would concede to Ra’avad where the non-belief is not due to a resolute decision, but merely due to ignorance.

But Shapiro says that this could not possibly be the Rambam’s stance. The Chazon Ish, he writes, “obviously never saw Guide 1. 36,”[54] where Rambam, according to Shapiro, condemns “as heretics those simpletons who do not know any better and take these biblical descriptions of God literally.”[55] Shapiro adds that the Chazon Ish “should be regarded as disputing with Maimonides, not interpreting him.”[56]upon investigation, there is no contradiction at all to Chazon Ish from the Moreh. Here are the words of the Moreh (Shapiro’s translation):

Accordingly there is no excuse for one who does not accept the authority of men who inquire into the truth … if he himself is incapable of engaging in such speculation. I do not consider as an infidel one who cannot demonstrate that the corporeality of God should be negated. But I do consider as an infidel one who does not believe in its negation; and this particularly in view of the existence of the interpretations of Onkelos and of Jonathan ben uziel, may peace be on both of them, who cause their readers to keep away as far as possible from the corporeality of God. [57]

The Moreh says explicitly that the reason why simple-minded people who believe in anthropomorphism are heretics is because they should have sought out the opinion of those men who are able to “inquire into the truth” and should not have relied on their own wisdom. Clearly, then, the Moreh opinion is that where these people have no one to seek out, they are not culpable as heretics. This is exactly what the Chazon Ish is saying.[58]

Shapiro says that the Chazon Ish is disputing the Rambam when the former says that an innocent disbeliever (tinok shenishba) is not a heretic.[59] However, the Chazon Ish is merely following the opinion of Rambam in Hilchos Mamrim who says the same:

A person who does not acknowledge the validity of the Oral Law is not the rebellious elder mentioned in the Torah … To whom does the above apply? To a person who denied the Oral Law consciously, according to his perception of things. He follows after his frivolous thoughts and his capricious heart and denies the Oral Law first, as did Tzadok and Baisus and those who erred in following them. The children of these errant people and their grandchildren whose parents led them away and they were born among these Karaites and raised according to their conception, they are considered as children captured and raised by them. Such a child may not be eager to follow the path of Mitzvos, for it is as if he was compelled not to. Even if later he hears that he is Jewish and sees Jews and their faith, he is still considered as one who was compelled against observance, for he was raised according to their mistaken path. This applies to those who we mentioned who follow the erroneous Karaite path of their ancestors. Therefore, it is appropriate to motivate them to repent and draw them to the power of the Torah with words of peace, and not to rush to have them killed.[60]

Abarbanel’s Position

In an attempt to list various authorities who took issue with Maimonides, Shapiro tells us that “[i]n Abarbanel’s mind, only limited attention should … be paid to Maimonides’ early formulation of dogma, and it would certainly be improper to make conclusions about his theological views on the basis of a text designed for beginners.”[61]

This is not what Abarbanel writes. In Abarbanel’s Rosh Amanah, an extensive work dedicated to the Principles, after twenty-one chapters of analysis in which he resolves twenty-eight questions which he initially posed on the Principles, the Abarbanel concludes:

Now if so, we have solved the 28 questions which we raised on the words of the great Rav in his Principles and in the Mitzvos which he presented in his works. It is clear from my words that everything that was uttered by him is correct without any twisting or crookedness, and that the thirteen Principles which he articulated are indeed Principles according to the precise wisdoms, as I have mentioned.[62]

Abarbanel could not have been any clearer in his support of the Principles. Apparently, Shapiro’s contention that Abarbanel disapproved of the Principles is based on a misreading of his words. Abarbanel explains why Rambam lists individually those Principles which could have been derived from other Principles. He writes that this is because Rambam wrote his Commentary on the Mishna[63] for those unable to make such derivations, unlike the Moreh which is oriented towards the more intellectual student:

Even though some of these Principles can be derived from the others, the great Rav saw fit to delineate them each as Principles, listing each Principle individually. For he did not present these Principles for the wise who know wisdom alone, but for the entire nation, from child to the elderly, and certainly according to what is necessary for the explanation of the Mishna. Accordingly, he detailed each praiseworthy belief and made each a Principle onto itself, for his intention was to perfect those men and women who were not perfect in intellectual insight. In addition, the Rav saw that there was a wisdom in the total number of the Principles, as I will mention.[64]

In other words, the Rambam listed the Principles for those who would not be able to derive the Principles on their own, even though, according to Abarbanel, many of the Principles are logical derivatives of the others. By listing them individually, Rambam attempted to ensure that even those whose thinking capacity was limited would have the requisite faith.

This explanation does not imply in the slightest way that the Principles are not a product of the Rambam’s true theological views. On the contrary, the entire work of Abarbanel consistently indicates, as above, that he believed that the Moreh and Principles are harmonious.[65]

Another Example

Another example of Shapiro’s proofs that Rambam’s theology differs from one work to another is the following. In his Commentary on the Mishna, Rambam states that “lack of belief in any of the Principles makes one a heretic.”[66] Yet, in his Mishneh Torah, he writes (Shapiro’s translation):

Whoever permits the thought to enter his mind that there is another deity besides this God violates a prohibition, as it is said: You shall have no other gods before Me … and denies the essence of religion—this doctrine being the great principle on which everything depends.[67]

This proves, says Shapiro, that one is not considered a heretic for such thoughts since the Rambam does not say that one who holds these beliefs is a heretic.[68] However, the very source he adduces clearly says the opposite. The words kofer be-ikar, used by the Rambam in this quotation, are a synonym for “heretic,” even according to Shapiro’s rendition of the words as one who “denies the essence of religion.”

If the Rambam writes that recognition of God as the source of all existence is a Principle upon which all of Judaism stands, it is obviously a Principle of faith.

II. SHAPIRO’S ANALYSES OF THE PRINCIPLES

I

t will be beneficial to review a number of Shapiro’s presentations of specific

Principles and determine if there is any evidence at all to support Shapiro’s claim that many traditional scholars believed “Maimonides’ Principles were wrong, pure and simple.” Space does not permit a discussion of Shapiro’s treatment of all the Principles; we will therefore focus on those presentations which are the most problematic. We will begin with the second Principle.

The Second Principle: The Unity of God

The second Principle teaches the absolute unity of God, and that it is unlike the unity of anything else. While acknowledging that no Jewish teacher has

openly disputed this, Shapiro goes on to say:

It is impossible to reconcile the kabbalistic understanding of God and his various sefirotic manifestations with the simple, unknowable God of Maimonides. … it is difficult for all but the most vigorous defenders of the sefirotic system not to see in it a departure from the doctrine of the unity of God.[69]

But investigation of the sources does not bear this out. Here is an example of one citation by Shapiro, from R. Moshe Cordovero:

At the start of the emanation, the Ein Sof [the Infinite], King of All Kings, the Holy One, blessed be He, emanated ten Sefirot which are from His essence, are one with Him and He and they are all one complete unity.[70]

However, if we read this in context, R. Cordovero writes something completely different:

וקודם יצירת העולם לא הוצרך אל אצילות....והיה נעלם בפשיטותו הקדוש והטהור, ואף כי האציל האצילות הזה הקדוש והטהור לא יצדק בו שום אות ונקודה וציור, כי אפילו כתר תחילת האצילות נשלל ממנו השם והציור, כ'ש וק'ו המאציל ממ'ה הקב'ה,

ובו אין אנו יכולין לדבר ולא לצייר...

Before Creation, [God’s] emanation was not necessary … He was hidden in His holy and pure peshitus [indefinability] and even though He was the cause of this holy and pure atzilus [emanation], it cannot be described by any letter, dot or image, for even keser [the first Sefirah] of atzilus is removed from any name and image; how much more so, the One who is the source of the emanation, the King of Kings, blessed be He, regarding Whom we are unable to speak or to imagine?

In other words, there is nothing about the emanations, or Sefiros, to contradict the belief in the One and unknowable God. Shapiro must certainly be aware of the extensive literature addressing why this kabbalistic concept is not a contradiction to the unity of God. See, for example, Shomer Emunim haKadmon, by a recognized kabbalist of the eighteenth century—who explains this in great detail.[71]

Shapiro concedes that the kabbalists themselves do not see their own ideas as contradicting the Principle. Shapiro, however, believes otherwise; in other words, he is saying that he knows what the kabbalists believe better than do the kabbalists themselves.[72] In any event, it would appear obvious that if the kabbalists exert themselves to explain how their ideas are not a contradiction to the unity of God, they cannot be adduced as illustrations of those who held that “Maimonides’ Principles were wrong, pure and simple.”

Rivash

In support of his assertion that the Sefiros are a contradiction to belief in the unity of God, Shapiro cites Rivash[73] as quoting a statement that: “whereas the Christians believe in three [deities], the kabbalists believe in ten.” However, this source says the direct opposite. The above argument is cited by Rivash in the name of a philosopher, but in the same paragraph, the Rivash accepts the explanation of a kabbalist that—the philosopher notwithstanding—there is no contradiction to God’s unity in the Sefiros, commenting on the explanation that it is tov me’od—“very good.” In other words, the Rivash says precisely the opposite of what Shapiro purports him to say. A glance into the original would have shown that there is no basis for Shapiro’s statement.

The Third Principle: The Incorporeality of God

This Principle affirms that God has no body, nor any aspects of a body. Says

Shapiro: “Although, as we shall see, the Bible and Talmud speak of a corporeal God, Maimonides’ philosophical outlook forced him to insist on divine incorporeality.”[74]

Here, too, Shapiro is saying that the Rambam’s codifications are a contrived formulation, based upon his “philosophical outlook”—but inconsistent with the Bible and Talmud. He writes that “it should be obvious to all that Maimonides’ insistence on God’s incorporeality contradicts a simple reading of the Bible. … indeed nowhere in the Bible does it state that God is incorporeal (or invisible for that matter).” [75] Shapiro must surely be aware that a belief that God has a body reduces Judaism to a form of idolatry, as the Rambam explicitly writes,[76] yet Shapiro insists that this is an authentic Jewish belief.

In his Hilchos Yesodey haTorah, the Rambam details the elements necessary to fulfill properly the Mitzva of belief in the unity of God (which we perform twice daily through the recitation of Shema Yisrael):

This God is One. He is not two or more, but One, unified in a manner which [surpasses] any unity that is found in the world. ...If there were many gods, they would have body and form, because like entities are separated from each other only through the circumstances associated with body and form. Were the Creator to have body and form, He would have limitation and definition, because it is impossible for a body not to be limited. ... Behold, it is explicitly stated in the Torah and [the works of] the prophets that the Holy One, blessed be He, is not [confined to] a body or physical form, as is stated [Devorim 4:39]: “Because God, your Lord, is the Lord in the heavens above and the earth below,” and a body cannot exist in two places [simultaneously]. Also [Devorim 4:15] states: “For you did not see any image,” and [Yeshayahu 40:25] states: “To whom can you liken Me, with whom I will be equal.” Were He [confined to] a body, He would resemble other bodies.[77]Shapiro says that Rambam is inconsistent with the Bible and Talmud even

though the Rambam cites specific verses as proofs of his Principles. Shapiro’s argument is that his own reading of the verses indicates that the very same verses, cited by the Rambam as a proof that God has no body, are indication that God has a body. For example, the Rambam adduces the verse which says “You have not seen any image” as proof. Shapiro interprets the verse differently:

“Ye saw no manner of form on the day that the Lord spoke to you …”, this is not a denial of divine corporeality, only a statement that God’s form was not seen.[78]

Similarly, Rambam quotes a verse in Yeshayahu, “To whom can you compare Me and and I will be like him?” as a textual source that Jews believe in non-corporeality. Shapiro cites the very same verse as evidence to the contrary. He writes that this verse “is not a denial that God has a form, only that this form is unlike anything else.[79] In other words, Shapiro has no qualms about saying that the Rambam got his translations wrong.

Shapiro follows the same approach to Talmudic sources. He seeks to prove that, according to the Talmud, God is corporeal from the passages which say that God wears Tefillin (Berachos 6a) and that Hillel compares his countenance to the image of God,[80], and from the numerous Talmudic discussions regarding tzelem Elokim.[81] The meaning of these passages has been explained and taught since Geonic times as allegorical, without the slightest suggestion that these passages might refer to God as corporeal.[82] To Shapiro, however, they are a discovery which challenges the Rambam’s third Principle. Are there no limits to academic hubris?

Rashi Was a Corporealist

According to Shapiro, there is reason to believe that Rashi as well was a corporealist. He bases his claim on Rashi’s comment to Shemos 7:5 and 14:31 on the verse referring to God’s “great hand.” Rashi comments that “great hand” is mamash—an “actual” hand. Shapiro claims that Rashi’s comment is “to prevent one from thinking that in this verse ’hand’ [yad] means simply ’power;’” he, therefore, says that it means a hand literally, indicating that Rashi believed in the corporeality of God.[83] This is a simple misreading. On the contrary, Rashi indicates that “hand” does mean “power,” as he states explicitly in his commentary to Shemos 14:31. When Rashi writes mamash, he means to preclude the alternate meaning of yad which is “domain.”

More revealing than the fact that Shapiro has misread Rashi is the fact that he has ignored the comments of Gur Aryeh, Mizrachi and Ramban,[84] who all explain Rashi quite clearly. Shapiro also neglects to cite Rashi to Shemos 15:8 where Rashi states clearly that all mentions of God’s traits or emotions are metaphorical:

The Scripture speaks of the Divine presence as if it were a human king so as to permit the people’s ear to absorb it in accordance with experience, so that they may be able to understand it.

Shapiro cites an additional proof that Rashi believes in corporeality from the latter’s commentary to Yevamos,[85] where the Sages say that all prophets looked through an unclear lens (aspaklariya) while Moshe Rabbeynu looked through a clear lens.[86] An examination of the original text shows that this is a gross misreading. The Talmud there records that King Menashe accused the prophet Yeshayahu of asserting that he saw God’s image when Yeshayahu said: “I saw God sitting on His throne,”96 whereas the Torah says, “For you have not seen any image.”[87] The Gemara explains Yeshayahu’s words by saying that his vision was through an unclear lens, and therefore, he imagined he was seeing God’s image, while Moshe Rabbeynu prophesized through a clear lens and made no such error. In other words, Moshe Rabbeynu had complete clarity of vision and realized that God has no form; Yeshayahu did not. The Talmud and Rashi’s commentary make this the only possible interpretation of the passage. Shapiro’s conclusion that it indicates corporeality is thus unwarranted.

To bolster his claim that the Torah and the Talmud accept corporeality of God, Shapiro cites an array of academics who take this position. For example, Alon Goshen-Gottstein, the founder of the Elijah Interfaith Institute,[88] makes the bold assertion that

there is absolutely no objection in all of rabbinic literature to the idea that man was created in the image of God’s physical form [and] in all of rabbinic literature there is not a single statement that categorically denies that God has body or form.[89]

The Rambam, however, says differently:

It is explicit in the Torah and the Prophets and God has no body or corpus.[90]

Therefore, the Sages said that any composition and separation [within God] is impossible; they said (Chagigah 15a), “Above there is no sitting or standing or back or tiredness.”[91]

Shapiro ignores Rambam’s own citations of numerous rabbinic sources that God has no body and prefers instead to give credence to unfounded claims by academics that there is no rabbinic support for Rambam’s Principle.

The Meaning of Aspaklariya

In another proof that there are sources for belief in God’s corporeality, Shapiro writes:

R. Israel Lipschuetz [in Tiferes Yisroel] writes that Moses, unlike the other prophets, saw, as it were, God’s reflection [in his aspaklariya]. Obviously, there must be substance to cause a reflection.[92]

This conclusion is without basis. In this passage, Tiferes Yisroel is explaining the commentary of Rambam to the Mishna in Keylim 30:2, where a utensil called an aspaklariya is mentioned. He understands Rambam’s commentary there to be referring to a mirror and not to a lens, as others have it. He applies this translation to the passage in the Sages, mentioned above, that prophets had a vision of God through an aspaklariya, or lens. He says this word means “a reflection, as of a mirror.”[93] It is clear from Tiferes Yisroel that the use of aspaklariya in this context is allegorical; indeed, Tiferes Yisroel refers to seeing prophecy through a mirror as כביכול—“as it were”—an expression used to indicate that an expression is not meant literally. This would be true whether the translation of the word is “lens” or “mirror.” R. Lipschutz’s translation has no bearing whatsoever on God’s corporeality. If there is any doubt about this, Tiferes Yisroel writes in the same paragraph:

It is impossible for a mortal to see the essence of God, even for Moshe Rabbeynu, regarding whom it is written, “And My countenance will not be seen.” It is only that all of Israel saw only a reflection of His essence, whereas Moshe Rabbeynu, as it were, saw the reflection as clearly as it is possible to see it.

Graven Images

Shapiro cites Rambam as clearly holding the opinion that angels are form without body.[94] He therefore questions why elsewhere, in Hilchos Avodah Zarah,[95] Rambam rules that one may not make images of the angels (codifying an undisputed Talmudic prohibition in Avodah Zarah 43b). He argues that, since one cannot make a graven image of something which has no body, the prohibition proves that Rambam is of the opinion that angels have bodies. Says Shapiro: “This is an example of Maimonides recording a law even though it did not fit in with his world view.”[96]

All of this has no basis. Angels may have no physical form, but still, one is forbidden to make a graven image which one declares is an image of an angel, just as one is forbidden to make a graven image of God even though God has no form or body.

R. Moshe Taku

Shapiro cites a work entitled Kesav Tamim written by R. Moshe Taku in the thirteenth century as rejecting Rambam’s third Principle and understanding God “as having an image and form, or at least able to assume these at will.”[97] At least one eminent scholar has shown without doubt that Taku never said this. Even if the work was written by R. Moshe Taku (and there is ample reason to suspect that it was not), there is not one source within this work where he writes that God is corporeal.[98] Here, too, is a conclusion which examination of the original source would have shown to be wrong.

The Fourth Principle: Creation Ex Nihilo

Included in this Principle of God’s priority is the concept of creation ex nihilo.

Shapiro claims that in Rambam’s Mishneh Torah he holds that denial of this belief does not render one a heretic. His proof for this statement is that, in the listing of heretical beliefs in Hilchos Teshuvah, “there is no mention … of creation ex nihilo.”[99]

However, the Rambam clearly cites one who denies creation ex nihilo as a heretic. One of the heretics he lists is “one who says that [God] is not solely the Prior One and the Creator of everything.”[100] Both Ra’avad111 and R. Yosef

Albo interpret this passage in this way.[101] Shapiro bolsters his contention by arguing:

Another place in which one might have expected some mention of creation ex nihilo is at the very beginning of the Mishne Torah. … it is striking how he seems to go out of his way to avoid any mention of Creation: “… know that there exists a First Existent, that He gives existence to all that exists….”[102]

Again, Shapiro’s expectations form his proofs. But one may properly ask, why should Rambam have addressed the fourth Principle while discussing the first?

Does the Moreh Believe in the Eternity of Matter?

Shapiro writes, “it is clear … in the Guide that even [Rambam] did not regard creation ex nihilo as a fundamental religious doctrine.”[103] However, R. Moshe Isserles (the Rema) writes that this is not the view of the Moreh in 2:13:

You should know, looking into the matter, that the foundation of our Torah is the belief in the Creation [חידוש] of the world, and upon this stake all the Torah depends. For this reason, the Rav writes in the Moreh (Part 2:13): “All those who are faithful to the Torah of Moshe Rabbeynu, may he be in peace, know that the whole world, that is, everything that exists other than the Creator, blessed be He, God brought out into existence from an absolute nothingness [העדר], and only God, blessed be He, existed and not anything else besides Him.[104]

And Abarbanel corroborates this view:

And from here, one can see that Creation [חידוש] of the world that the Rav

[Maimonides] believes is absolute Creation [חידוש המוחלט] that was created

in the wake of absolute nothingness[האפס המוחלט], unlike the opinion of Plato who believed in eternal matter … as the Rav writes in the Moreh 2:13 … “our Sages said without a doubt this is the foundation of Moshe

Rabbeynu’s Torah, and it follows upon the Principle of God’s unity.”[105]

Shapiro points us[106] to Moreh 2:26 and 2:30, where Maimonides explains two obscure passages in Chazal regarding Creation.[107] According to Shapiro, Maimonides believes these passages “might refer to the eternity of time,” which “according to [Rambam] … also means the eternity of the world.”[108] Shapiro notes R. Eliezer’s “apparent acceptance of the Platonic position.”[109] Though these passages are cryptic and inconclusive, Shapiro concludes that because “Maimonides discusses at length the Platonic view”[110] and “nowhere in the Mishneh Torah does Maimonides mention creation ex nihilo,”122 it follows that “we seemingly must conclude that Maimonides accepts the Platonic position as consistent with prophetic teaching.”[111]

Once again, Shapiro has failed to note the specific approach of the Moreh, which is to present the Torah from a philosophical perspective. As the Rambam

writes:

And know that the great Principle of Moshe Rabbeinu’s Torah is that the world is created [מחודש]; God formed [יצרו] and created this after absolute nothingness [העדר המוחלט]. And if you see that [my discussion] revolves around the concept of the world’s eternal existence according to the philosophers, this is only to prove absolutely the existence of the exalted God, as I have explained and clarified in the Moreh.[112]

In other words, although it is true that existence came into being ex nihilo, Rambam in the Moreh is discussing the matter from a philosophical standpoint, to demonstrate the existence of God through logic accepted by the philosophers.

Ibn Caspi, cited by Shapiro[113] as rejecting the classification of ex nihilo as a mandatory Principle, makes this same distinction in the same chapter as cited by Shapiro:

It is clear from all his [Maimonides’] words … his intent; that this world, whether it is created or eternal, either option is possible. However, prophecy, meaning to say the Torah and all the Prophets, decide between these options, and we follow that directive, because the soul of the Prophet is above logical insight.[114]

Thus, although philosophically one cannot prove that existence came about ex nihilo, the Torah viewpoint is definitely that it did and we follow the Torah which is more reliable than philosophy as the ultimate decisor as to what constitutes true faith.

Shapiro fails to take note of the opening of the Rambam’s discussion of Creation in the Moreh:

The outlook of every believer in the Torah of Moshe Rabbeinu is that the world—as a whole, meaning everything in existence other than the exalted God—was brought into existence by God following absolute and total nothingness … and He brought all these existent things into existence, as is, with His desire and will, from nothingness.

The plan of all those who follow the Torah of Moshe and Avrohom Avinu, and all those who follow in their path, is to know that nothing eternal exists together with God. [115]

Further, in the same chapter as cited by Shapiro, Rambam writes:

I have already made known that the foundation of all the Torah is that God brought the world into existence from nothingness, without a beginning in time.[116]

These citations place in doubt Shapiro’s assertion that “it is clear … in the Guide that even he did not regard creation ex nihilo as a fundamental religious doctrine.”[117]

Nevertheless, based on assumptions contradicted by explicit passages in the Rambam, Shapiro concludes:

Having thus seen[118] that Maimonides himself was fully prepared to deny creation ex nihilo, there is simply no way one can take seriously his contention that someone who even doubts this Principle is a heretic. As to his reasons for saying something he does not really believe, I will return to this … [119]

Shapiro has made a leap from a careless reading of the Rambam[120] to a misrepresentation of his teachings.

This methodology of Rambam study seems to be the approach of Shapiro whenever the text indicates apparent inconsistencies.[121] Rather than attempting to delve into understanding the text, Shapiro’s immediate solution to any difficulty is that the Rambam (1) changed his mind,[122] or (2) was speaking to beginners,[123] or (3) was concealing his true thoughts,[124] or (4) was providing the masses with the message they needed to hear.137

The Fifth Principle: Prayer Is to God Exclusively

Shapiro’s critique of this Principle, “One may pray only to Him,” is another illustration of his methodology. Shapiro focuses on the fact that the Rambam included in this Principle the idea that angels and celestial bodies are unworthy of worship “because they have ingrained natures and there is no judgment or free choice in their actions.”[125]

Rambam seems to say that angels have no free will, a subject discussed by many commentaries.[126] Shapiro says the Rambam is wrong because of passages in Torah and Chazal which explicitly attribute independent decision making to angels. The position of the Rambam, Shapiro says, is to disregard these passages because: “his [Rambam’s] views on this matter were influenced by Greek philosophy” and therefore, he “would either reject or, more probably, interpret any objectionable rabbinic passages allegorically.”[127] In other words, the Sages held that angels may be prayed to, while Rambam, under the influence of Greek philosophy, disagreed with them.

But even this opinion expressed in the Rambam’s Principles, is not, in Shapiro’s eyes, the former’s final view, for, says Shapiro, the Rambam later changed his mind. As Shapiro puts it, “Indeed [once again], it appears that

Maimonides later changed his view from that expressed in this Principle.”[128]

Shapiro cites Moreh 2:7, a “passage [that apparently] contradicts Maimonides’ statement [about angels] in the Fifth Principle.”[129] According to Shapiro, Maimonides also contradicts this Principle in his Mishneh Torah[130] and in his Letters.[131] Regarding this last contradiction, Shapiro suggests that Rambam is “[merely trying] to get a point across,” and “it is axiomatic in Maimonidean scholarship that … such popular works do not necessarily represent Maimonides’ true view.”145 No attention is paid to the fact that these contradictions have “gone unnoticed”[132] in rabbinic literature throughout the ages.

But a more careful look at Shapiro’s claims show that they are unfounded. As noted in our introduction, it is axiomatic to Torah scholars that Rambam was well aware of the sources cited in Torah and Chazal indicating that angels can be punished, rebel and err. Rather than positing that the Rambam ruled against the Sages’ opinion because he was “influenced by Greek philosophy,”[133] would it not be more likely that the Rambam understood these sources differently from Shapiro?

The explanation of the Rambam lies in the answer to several basic questions about the idea of prayer to angels in the fifth Principle which Shapiro fails to address. These are: 1) Why is the will of angels included in this Principle? 2) Why does Rambam group the capabilities of angels together with idolatry? and 3) Why should this idea be fundamental to Judaism?

Throughout the Moreh, the Rambam emphasizes how understanding the act of Creation, the precedence of God and His complete autonomy separates us from the Greeks. The fourth Principle teaches that God created the universe with His will (רצון[134]) and that this world is a vehicle where this will is expressed. Only a creation that is ex nihilo—brought about without external cause—derives from a pure will, one uninfluenced by anything else, and only it expresses the fact that God is not bound by any rules or natural limitations.

That God is the only One with pure will is also the basis of prayer (which is why the fifth Principle follows upon the fourth). Prayer is, in essence, the entry into a relationship whereby man hopes to elicit God’s will through service and request. Angels have many capabilities, but they cannot serve as an address for true prayer since their powers do not stem from a pure, autonomous will, but rather are mere functions of forces already imbedded within them.149

Nothing in any of the sources cited by Shapiro which attribute power to angels even remotely contradicts this idea. Whether angels have powers or not is irrelevant. What is relevant is that they have no autonomous will and they have no capacity to effect any change in the world. Consequently, one cannot pray to them. In fact, a study of Shapiro’s citations in their entirety will show that this is the issue addressed by the fifth Principle.

This explanation answers the questions posed above. The fifth Principle says that we may not pray to angels because there is only one autonomous will in the world, that of God. One who prays to angels is declaring that angels also possess this form of will, an assertion which is the equivalent of idolatry.

Shapiro cites authorities who dispute the fifth Principle. Among them is Ran, in his Derashos haRan;[135] Shapiro describes him as another dissenter from the Rambam’s view that one is forbidden to prostrate oneself before angels.[136] Yet, in the same cited Derashah, a few paragraphs later, Ran explains why service to angels is likened to idolatry, in full agreement with the Rambam:

“You shall not bow down to their gods nor worship them.” Because I think that the source of idolatry was because they thought that the angels and heavenly forces have power to benefit or to harm if we can access their wills. However, the error which caused this …[137]

Similarly, Shapiro cites Abarbanel in Rosh Amanah, chap. 12, as opposing Rambam’s view regarding worshipping angels. But, in the very same chapter as the one cited, Abarbanel explains why one is not permitted to pray to angels:

The blessed God acts willingly and is unlike other beings in existence among the angels, constellations, stars, and elements and what they form, for they all are appointed to their tasks, and have no control or desire to do what they do. But the blessed God acts according to His will and desire, and therefore all prayer and service, praise and glory, are directed to Him.153

Shapiro also cites[138] Albo in Sefer haIkarim as one who sanctions service to an angel. But Albo says the following:

The angel Yerukami can cool, and the power of Gavriel is to warm, only with the will of God. … For the power of the supernal forces is limited, and none of them can do something except that which was ingrained in their nature, according to the understanding of the recipient, not as an autonomous will. … Therefore, prayer to it [the angel] is not proper at all, for its acts do not stem from its will but only from God, for the acts which come from Him come from will, and He has the power to will and not to will, to do something and its opposite, and to do kindness without reason, whether the recipient is worthy of this, or not worthy, as long as he prepares himself through prayer.[139]

These three classic authorities whom Shapiro cites many times in support of his thesis that “Maimonides’ Principles were wrong, pure and simple” agree explicitly with the Rambam that there is a prohibition to pray to angels.

Shapiro also claims that the Moreh 2:7 “directly contradicts Maimonides’ statement in the Fifth Principle.”[140] This is the quotation from the Moreh (Shapiro’s translation):

The spheres and the intellects apprehend their acts, choose freely, and govern, but in a way that is not like our free choice and our governance, which deal wholly with things that are produced anew.

Shapiro acknowledges here that, according to Rambam, the “free” will of angels is not like that of man, for humans

sometimes do things that are more defective than other things, and our governance and our action are preceded by privations; whereas the intellects and the spheres are not like that, but always do that which is good, and only that which is good is with them.[141]

Shapiro ignores this important qualification of the will of angels, even though it means that the Rambam is not contradicting himself in his Moreh.

In this case, Shapiro’s translation has rendered opaque the Rambam’s crucial words. Rambam is explaining that the “free”[142] choice of angels is not truly free choice, for only that of man[143] is preceded by non-will (“העדר”) and hence only man creates a new will with his decisions, creating anew[144] a portion of the world where God’s will is manifest, bringing this potential to life. The angels can create nothing new—their functions are considered to have already been fully actualized. Hence, there is no prayer possible toward the angels and, if so, there is no contradiction in Rambam at all.

The Seventh Principle:

The Prophecy of Moshe Rabbeinu

Shapiro assumes[145] that his reader already understands the Principles, and rather than explaining each, he focuses instead on those scholars who opposed them. However, nearly all of Shapiro’s critiques of the Principles are not clear disputes, but only disputes suggested by Shapiro, based upon his own inadequate presentations of the Principles. Without prior analysis of the Principles themselves, the reader cannot judge if Shapiro’s sources actually contradict the Principles.

For example, the seventh Principle describes the unique nature of the prophecy of Moshe Rabbeinu. Rambam explains in great detail, and Abarbanel elaborates, upon the unparalleled nature of Moshe’s prophecy. Shapiro presents ideas of Chazal which seem to disagree with the Principle. He writes, “[A] couple of strange Midrashim, dealing with Balaam and Samuel … seem to take a different approach.”[146] For example, one Midrash says, “’And there has not arisen a prophet [like Moshe] since in Israel’ … —In Israel there has not arisen one like him, but there has arisen one like him among the nations of the world … Balaam …”[147]

Shapiro lists a group of major authorities who understood the Midrash as referring to certain commonalities between the prophecies of Bil’am (Balaam) and Moshe Rabbeinu. Among these authorities are Ramban,[148] Recanati,[149] Akeydas Yitzchok,[150] Abarbanel,[151] Ya’aros Devash[152] and HaKesav ve-haKabbalah.[153] Each of these sources, and those of other classic commentators, hold the Midrash to be describing a specific parallel between Moshe and Bil’am— but none of these classic responses entertain the thought that Bil’am was greater than Moshe, or that this Principle was contradicted.[154]

However, Shapiro dismisses these commentators and decides instead that the Midrash[155] must be taken at face value. As for the various interpretations, they are “post-talmudic authorities [who] reinterpret this Midrash so that Bil’am will not be regarded as Moses’ equal.”[156] Again, this is nothing but academic presumption.

Shapiro adduces a source in support of the notion that all the “reinterpretations” are wrong. His source: “There are those [who do not ’reinterpret’ but] do indeed take [this Midrash] in its simple sense. For example, R. Samuel of Roshaina (twelfth century) quotes the midrash without comment.”[157] In other words, the teachings of all the major classic commentaries cited above understood that this Midrash does not in any way challenge the idea of Moshe Rabbeinu as father of all the prophets. Yet, says Shapiro, these teachings are wrong and merely “reinterpret” this Midrash. Sefer Roshaina trumps all of these commentaries.

But this source is non-existent. Here is the precise comment of R. Shmuel miRoshaina:[158]

ולא קם נביא עוד כמשה: אבל באומות קם, שלא יהיה להן פתחון פה, וזהו בלעם

No prophet stood up like Moshe: But, among the nations of the world, one stood up so that they have no explanation [for their misbehavior], and this is Bil’am.

All this obscure commentator has done is to cite verbatim the Midrash without comment. In fact, nearly all of his work consists of terse citations of Chazal without any commentary. It should be obvious that proof from the omission of commentary by an author who omits all commentaries is meaningless and absurd.

Shapiro adduces further support for his position from Abarbanel. He says, “Abarbanel states plainly that Maimonides’ principle contradicts this rabbinic teaching about Balaam.”[159] Abarbanel’s Rosh Amanah is devoted to the scrutiny of each of the Rambam’s Principles—questioning and challenging wherever difficulties are found. After describing in perfect detail the Rambam’s seventh Principle, and expounding upon the unique nature of Moshe Rabbeinu’s prophecy, Abarbanel makes clear why this proves the eternity of Torah. He says:

Establishing the eternity of Torah is compelled by the unique prophecy of Moshe Rabbeinu which surpassed all other prophets. His prophecy was without force of imagination, and it is without doubt … that God wanted that no other prophet will ever arise to add to his words, for he knew God directly [פנים אל פנים], while all others [prophesied] through intermediaries. How can one who hears God’s words through intermediaries hear something that the Prophet who spoke to God without intermediaries did not? This is as the verse states: “and no prophet will arise [like Moshe].” And if so, there is no doubt that another prophet could add more [to the Torah].[160]

After this clear support of the Rambam’s seventh Principle, one wonders where Shapiro discovered that Abarbanel “states plainly that this principle contradicts this rabbinic teaching about Balaam”? But he does seem to have a source,[161] and this is in Abarbanel’s commentary to the Moreh 2:35. The Rambam explains there the unique nature of Moshe Rabbeinu and his prophecy, and adds the following:

Evidence in the Torah that the prophecy of Moshe was different than that of all his predecessors is the verse “and I appeared to Avrohom … but my name Hashem was not made known to them.” The Torah has made known that his grasp of matters was not like that of the forefathers, but greater, and certainly greater than all those who preceded them. As to his prophecy being greater than all those who follow afterwards, the Torah says, making it known, “And no prophet will arise in Israel like Moshe,” who knew God directly. The Torah has clarified that the understanding of Moshe surpassed that of all subsequent prophets in Israel, a Kingdom of Priests and a holy nation with God’s Presence among them; certainly [he surpassed] those among the other nations.

To this, Abarbanel comments:

And this is opposed to what the Sages said: “There did not arise in Israel, but amongst the nations one did arise—Who was that? Bil’am.”

Rambam has interpreted the verse, “And no prophet arose in Israel like Moshe,” to mean that even in Israel, the most sanctified of nations, no prophet equal to Moshe arose, and then added a comment: “... and certainly in other nations, which do not possess the sanctity of Israel.” Abarbanel comments that this interpretation is different from that of Chazal who interpret “in Israel” to mean exclusively in Israel, but that among the nations, there will arise someone like Moshe.

Abarbanel is not disputing the Principle that there will be no prophet like Moshe; he is only commenting that the proof text cited by the Rambam is interpreted differently in Chazal.[162] Abarbanel himself actually cites the same verse[163] in his Rosh Amanah to indicate that indeed no greater prophet than Moshe will ever arise. Hence, Abarbanel is not interpreting this teaching of Chazal to mean literally that another prophet among the nations will be as great as Moshe. Abarbanel must agree with all the above commentaries and interprets the Midrash to mean only that there are certain commonalities between Moshe and Bil’am. Shapiro’s source that Abarbanel disagrees with the Rambam does not exist. Shapiro must certainly have known Abarbanel’s position as stated in Rosh Amanah, but for some reason failed to inform his readers about it.[164]

Albo, in a comment noted by Shapiro,[165] gives both of these interpretations to the Midrash:

God conceded to him [Moshe Rabbeinu] as regards the elevated stature that he requested, and for this reason the text testifies at the Torah’s end that no other prophet in Israel will arise like Moshe, meaning to say that, even from among Israel, which is the nation chosen for prophecy, there will never arise another like him, as he was promised, and certainly not from among the other nations who are not worthy of having prophecy applied through them. And when the Sages said, “And there will never arise among Israel a prophet like Moshe”—from Israel there will not arise, but from among the nations there will arise—and who will that be?—Bil’am,” they said this to acknowledge that just as the prophecy of Moshe was for Israel, as we have explained, so, too, Bil’am reached a level of prophecy, though he was only a sorcerer, only for Israel, in order to bless them, but this is not to equate the level of prophecy of Bil’am to that of Moshe, God forbid.[166]

Albo, too, agrees with the seventh Principle; nevertheless, Shapiro cites him as contradicting it.[167]

The Eighth Principle: All the Torah Is Divine

When the Rambam cites in this Principle that “all the Torah we have is from God,” Shapiro cites this view as holding that the Masoretic text established by Ben Asher, which is a preferred text according to Rambam,[168] is exactly the same as the Torah that Moses presented to the Jewish people and that whoever disagrees with this “is a heretic with no share in the world to come.”185

Shapiro then goes on to show that the Rambam is wrong on the basis of the varying opinions as to the veracity of this text.186 Furthermore, the final eight verses of the Torah which speak of the death of Moshe Rabbeinu were written by Joshua, according to some opinions. According to Shapiro, this idea also contradicts the Principle.187

However, Shapiro has set up a straw man and has then proceeded to knock him down. The Rambam never said that disagreement with the text of Ben Asher is heresy. The Rambam said to rely on it only in matters of sesuma and pesucha parshios (open and closed sections of the Torah), but not for determining other variants in the text, so that a Sefer Torah is not invalid where it disagrees with Ben Asher’s text.188

Thus, the text of Ben Asher was to be relied upon only regarding questions of opened and closed sections and in the formatting of the songs in the Torah. For all other questions, even for deficient or superfluous words (חסר ויתר) where the Rambam rules that a mistake would render the Sefer Torah invalid,189 we would not follow the ruling of Ben Asher, but rather, as is clear in the passage of Maseches Soferim cited by Shapiro, we rule according to the majority.190 It is only in these cases of opened and closed sections and the formatting of the songs where, as he stated, there was great confusion and no ruling could be made, that we rely on the codex of Ben Asher.

Furthermore, Rambam never claimed that believing that every word of the Torah text that we possess is the same as the one given to Moshe is a necessary element of Jewish belief. We are enjoined to accept the Torah which we know as Torah. However, if someone has a tradition that a word of the Torah is different, this tradition is for him the Torah which he knows and believing it is not heresy.

As the Rambam states clearly in this Principle, both the Written and Oral Torah (Torah She-be’al Peh) are the same in this respect. One who refuses to accept the Oral Torah or denies the authority of the Sages is explicitly considered

עי’ מנחות ל’ ע’א, חידושי הגרי’ז )על הש’ס( שם. 187

188 See Responsa of R. Avrohom ben HaRambam 91 which explains that Sifrey Torah written in accordance with mesorah but differently than the Rambam’s list of pesucha and sesuma, would not be invalidated. Apparently, when Rambam writes ועליו סמכתי regarding the Sefer Ben Asher, he was ruling only with regard to the most preferable model to follow where the mesorah regarding pesucha and sesuma was inconclusive. R. Avrohom ben HaRambam is not arguing with his father in this responsum, one actually cited by Shapiro on p. 97.

189 Hilchos Sefer Torah 7:11.

190 Shapiro cites (p. 102, note 80) R. Meir Abulafia in Masores Seyag laTorah, who states explicitly that his rulings were based upon the majority. Teshuvos haRashba (HaMeyuchasos) #232 and Meiri, Kiryas Sefer, ma’amar 20, cheylek 3 concur.

a heretic by the Rambam.[169] Yet virtually every page of the Talmud contains disputes over what constitutes the true Oral Torah. Certainly, the Rambam never meant to write half the disputants in the Talmud out of a share in the World to Come. In fact, none of the disputants is denying the Oral Torah; each is claiming merely that his understanding of the Torah is the correct one.

Searching out the truth of Torah is something the Torah itself enjoins us to do whenever there is a doubt: “and you shall act according to what they [the Sages of your times] teach you.”[170] We must do our best to apply ourselves and discover the true meaning of the Oral Torah, and when there is a doubt, we must follow the majority ruling. As the Sefer haChinuch explains, the Giver of the Torah knew when He gave the Torah that it would be impossible for there never to be differences of opinions regarding the correct interpretation of the Torah. In such cases, we are commanded to follow the opinion of the elders of our times.[171]

The same principle applies to the Written Torah. If two Sages are in dispute as to the correct text of the written Torah, we are enjoined to follow the majority opinion. As long as the disputants are attempting to arrive at what they believe is the accurate tradition of the Torah, they are not heretics. A heretic is someone who, given the accepted opinion of the Sages of the Oral Law, nevertheless denies its veracity.

The same principle applies to variant texts in the Torah. When a community accepts a text because that is its tradition, they are doing what the Torah enjoins them to do, namely, to adhere to their traditions. It is heresy only if they deny the veracity of a word of the Torah which they know is part of the written Torah.

Thus, in response to Shapiro’s question as to how there can be variants in the Torah, the answer is that the Torah is what the Rabbis and their students say it is. The halachic process determines it as such, although no text was ever delineated as authoritative.

One of Shapiro’s purported contradictions to the eighth Principle is that the Tanna Rabbi Meir is reported to have had a Torah scroll where the word עור in “״ כתנות עור was spelled אור. This, Shapiro says, is a contradiction to the Rambam’s Principle, for otherwise Rabbi Meir was a heretic.

But the same Rabbi Meir said: “Is it possible that Moshe gave the Torah while it was missing one letter?”[172] Obviously, if R. Meir argues that Moshe Rabbeinu wrote every word of the Torah, and the same R. Meir authorized a variant text to the Torah, it must have been because he felt that this text was the correct tradition, and someone who follows his tradition is not denying the written Torah. (Besides these considerations, there are other allegorical explanations of Rabbi Meir’s text-change from “אור” to “עור”.)

This same explanation applies to other sources which Shapiro cites as contradicting the Rambam’s Principle. Regarding those Talmudic opinions that the last eight verses in the Torah were written by Yehoshu’a,[173] Shapiro writes, “Quite apart from the issue of Mosaic authorship,[174] positions such as these contradict the Eighth Principle’s additional affirmation that all verses of the Torah share the same sanctity.”[175] Shapiro assumes that if the last eight verses were written by Yehoshu’a, they do not have the same sanctity as the rest of the Torah. This assumption has no source; these verses are treated differently only with regard to the manner in which they are read in a congregation. These verses may have been written by Yehoshu’a, but they were still given by God to the Jewish people as part of the Torah and are thus part and parcel of it.

Shapiro’s assumption regarding this Principle may lie in a citation he makes of a professor[176] who describes the eighth Principle as saying that “every single verse of the Torah was received directly by Moses from God, like a scribe taking down dictation.” But this is not what the Rambam actually says:

For this Torah which we have in our hands is the Torah given to Moshe and that it is entirely from the mouth of God, i.e., it came to us from God in a manner which we metaphorically call “speech,” although we do not know how it came to us, only that it reached us through Moshe of blessed memory, and that he was like a scribe for whom one reads and he writes all the occurrences, the stories and the commandments, For these reasons, he is called “engraver” [of law].199

The Rambam clearly states: “We do not know how it came to us”—ואין ידוע האיך הגיע לנו—and never asserts the revelation to be uniform or unvarying; so how can we state definitively that attempts to explain the details of this process and to clarify the precise message “directly contravene”’ something the Rambam has not explained here?